As we pull on our blue jeans or snuggle into our flannel sheets at night, few of us stop to think about the fabric involved. Modern science has given us a number of synthetic fabrics, but there was a time when cotton was king. Cotton culture and processing were vital to southeastern farmers and textile mills. Today’s blog is lengthy, and much more personal than my average post. I beg your indulgence.

Cotton’s history is inextricably entwined with the history of black slavery. I will leave that subject untouched and relate how it impacted my family and my husband’s family in a post-slavery world.

Cotton was a godsend for the southeast farmer who struggled to survive in the 1920s. Another choice was tobacco. North Carolina trended toward tobacco farming, while South Carolina leaned toward cotton. Landowners of small tracts could split planting between cotton and food crops in a bid for self-sufficiency.

My husband’s parents worked in textile mills for forty-plus years. My mother-in-law worked in the Spartan Mills office, recording weights of received shipments. My father-in-law worked in the weave room. His aptitude for technology led him to a supervisory position, where he embraced new electronic devices, a precursor of today’s computer systems. Being around loud machinery cost him most of his hearing ability, and he spent the last decade of his life in near-deafness. They were honest people with a strong work ethic. Without their frugality and hard work, my husband and I could not enjoy our current lifestyle. The table in my foyer holds a weaving shuttle and a memorial cotton bale to remind me daily of their sacrifices.

My mother was born in 1920, the second of four children to a farmer with small land holdings. Her father, Tom Brown, worked hard to make a living for his family. He supplemented his income with construction work when it was available. He planted cotton as well as corn, watermelons, and butter beans. He depended heavily on his children to help with field work. This was normal. The children of farming families were expected to participate in supporting the family. My mother related how her hands hurt when ripe cotton bolls (the mature flower and its resulting fiber) were harvested. The bolls ripened in late October, and cold temperatures hurt her hands as much as the sharp husks from which the ripe cotton bulged. Gloves were a luxury reserved for wealthier folks. The Brown family could not afford to take their cotton to a gin for seed removal, so every night before they were allowed to sleep, each child was required to fill their shoes with cotton seed they pulled from their portion of the daily harvest. The older the child, the bigger the feet, and the more labor required before the evening rest. A single boll usually has twenty-six seeds. The fibers adhere firmly to the seeds, so removal was not an easy task.

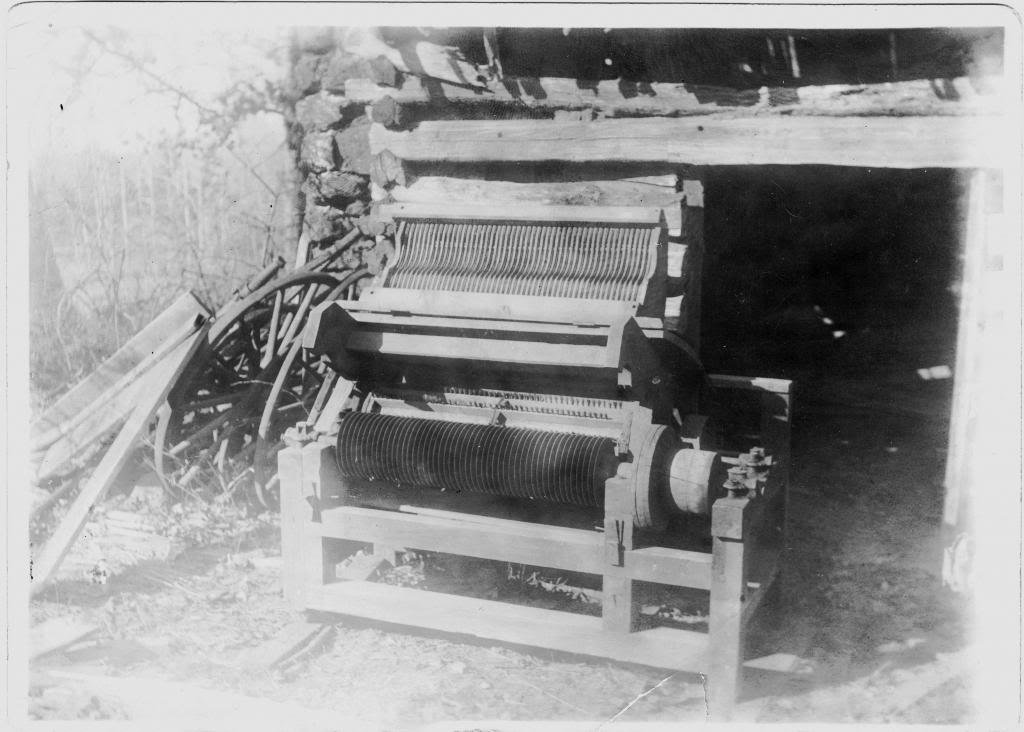

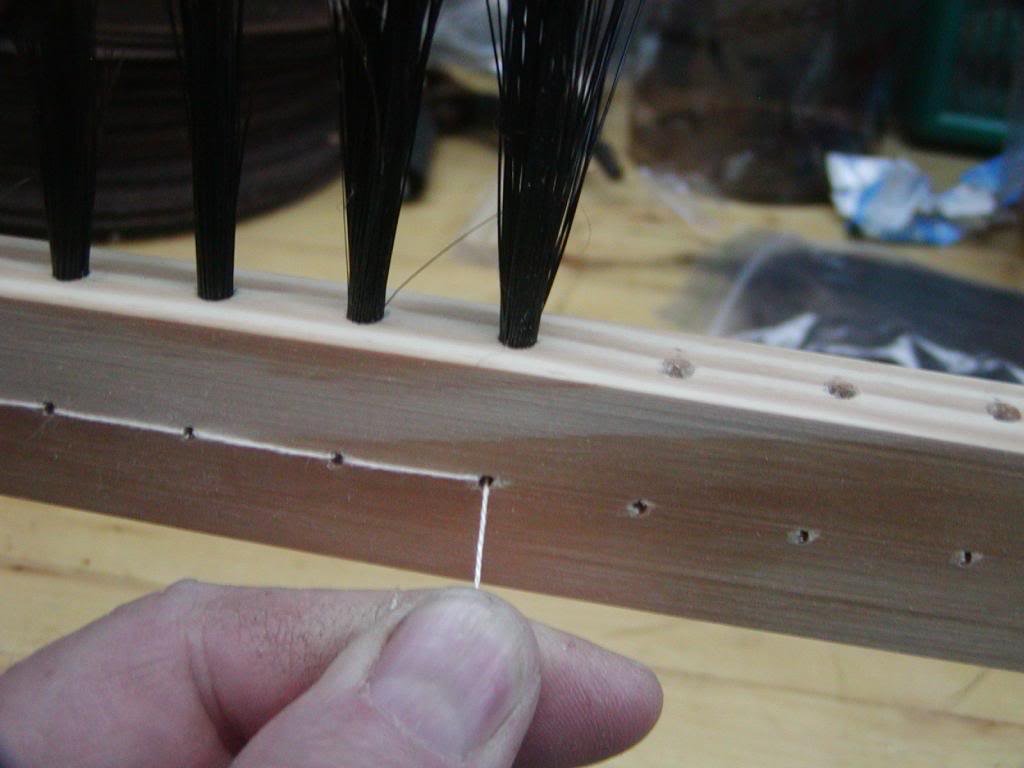

Sadly, an 1844 Griswold cotton gin sat, unused, underneath the lean-to of a barn on the Brown property. It was inherited by our grandfather in a non-working state. Grandfather Brown did not have the time, money, or technical expertise to return it to a working status. My brother, Jerry Neely, took possession of the rotted timbers and few metal parts that remained of the gin after Grandfather Brown passed. Jerry planned to restore the gin to its original operating state. He approached the restoration with unparalleled patience, using 1920’s photographs of a similar gin, and repeated machinations with AutoCAD, an engineering and design software program. He eventually brought the gin back to perfect running order. It is now housed at the Fountain Inn (SC) History Museum. The ginning mechanism itself consists of fifty 9-inch saw blades paired with brush bars. The brushes are made of hog bristles, counted individually and tied by hand. At the time of the restoration, the only source for these bristles was in the country Latvia. To fully appreciate the tedious, painstaking nature of the tying task, you should know that my brother has hands roughly on the same scale as Andre The Giant.

This is all that was available before the restoration began:

Restoration underway

Ready to Gin

Boll weevil model in the Cotton Museum

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, pronounced gu-SIP-ee-um her-SOO-tum) is still grown in South Carolina, over 250,000 acres in the lower part of the state. The plant is beautiful in flower, closely resembling Hibiscus blooms.

The South Carolina Cotton Museum is located in Bishopville, SC. It is worth a visit to see the enlarged model of the notorious boll weevil. The boll weevil’s lifespan is only three weeks, but over a two-year span in the early 1920’s, it wiped out 70% of the Carolina cotton crop. Boll weevils are rare now but will never be completely eradicated. Vigilance and monitoring are necessary to prevent a resurgence. That is why it is illegal to grow non-commercial cotton in SC without a permit.

While we all think of cotton in terms of the fabric woven from its fibers, the entire plant is useful. Pressed seeds produce oil, and the plant can be used as animal fodder. The next time you grab a bleached, pristine white cotton ball to remove your makeup, consider its origin.

Fun facts: A typical cotton bale weighs 480-500 pounds. Our money is 75% cotton. Cotton is a member of the Mallow plant family. The plant is a heavy user of nutrition, and soil must be regularly amended with fertilizer to avoid depletion.