Gardeners have a special affinity for rare plants like the Blue Poppy (Meconopsis) or the Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha). In March and April, plant enthusiasts travel for miles to Devils Fork State Park in Salem, SC to catch a glimpse of the rare, prized Oconee Bell plant in bloom. This wildflower occurs naturally in only seven counties in the US.

The Oconee Bell plant (Shortia galacifolia, pronounced SHORE-tee-uh guh-lay-sih-FOE-lee-uh) was discovered in 1788 by French botanist André Michaux. Unfortunately, he did not record the exact location of his discovery. Fifty years later, an American botanist named Asa Gray became obsessed with finding the plant in its native environment. He searched for 39 years without success until 1877, when a 17-year old boy who was helping his herbalist father collect specimens, saw the plant, could not identify it, and sent a specimen to a botanist in Rhode Island, who in turn sent it to Gray for identification. This sweet story illustrates a few points: (1) Always mark plant locations so you know where to find them. Use your mobile phone’s compass app to record GPS coordinates. (2) Force your teenagers to go into the woods with you. They bring a fresh set of eyes. (3) If you seek a special plant, don’t stop looking until you have found it.

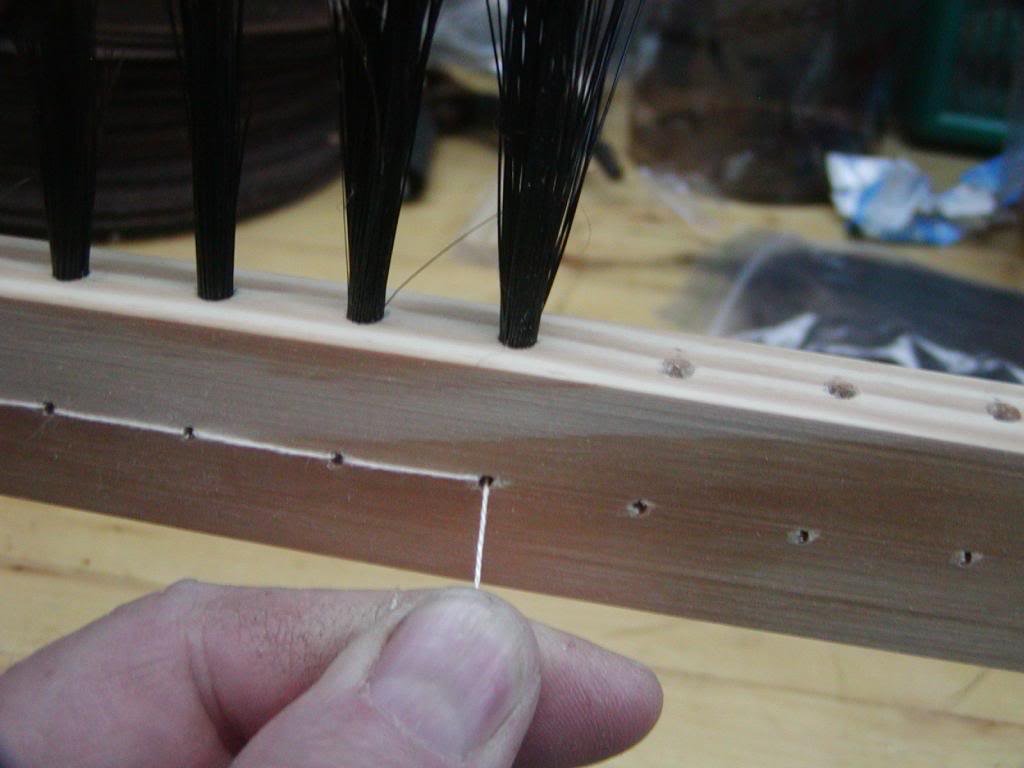

Oconee Bell grows in damp, partly shady areas, usually near a creek. It spreads by rhizomes and also by seeds. It can make a beautiful groundcover where the conditions are right. Small pinkish buds open to white one-inch flowers with serrated petals that look as if someone trimmed them with pinking shears. The foliage is handsome when the plant is not in flower, and it turns a pretty shade of dark red in winter. Plants reach a maximum height of eight inches. They are normally found in areas that have been disturbed and are in regrowth. Once a tight overhead canopy establishes, the preferred environment no longer exists and plants make their way toward more favorable destinations.

These plants are considered endangered and should never be gathered in the wild. Professional botanists have planted seedlings in numerous places to avoid possible extinction. You can see them in spring in the NC Arboretum wildflower beds.

Oconee Bell buds. Image by jackollis CC BY-NC 4.0